A Tunnel to the Rocky Fork?

By Alan Wigton

1896 headline: “Miss Mary F. Huber, Precipitated…Into the Bed of a Mill Race Long Since Abandoned”.

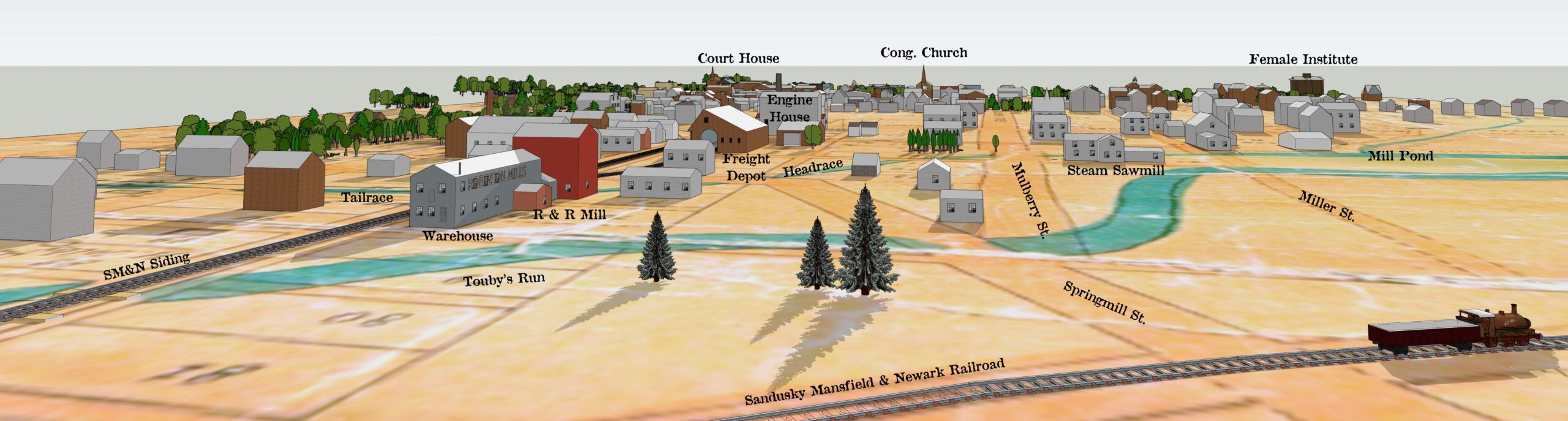

A water mill at the center of Mansfield’s north end once stretched water channels across the entirety of the city from its dam at Bowman Street to the Rocky Fork at Orange Street. The “old mill race” that was left behind after the mill’s 1869 demise was a blessing and a curse for long years after.

The Robinson and Riley mill was the first water-powered grist mill in the city of Mansfield. Local investor Henry Leyman built the mill. John R. Robinson and James Asher Riley bought it in 1843, “improved” it, and operated it through the 1850s. It was on Toby’s Run alongside the railroad from Sandusky to Mansfield that Robinson built in 1846, and within sight of his new home at Oak Hill Cottage.

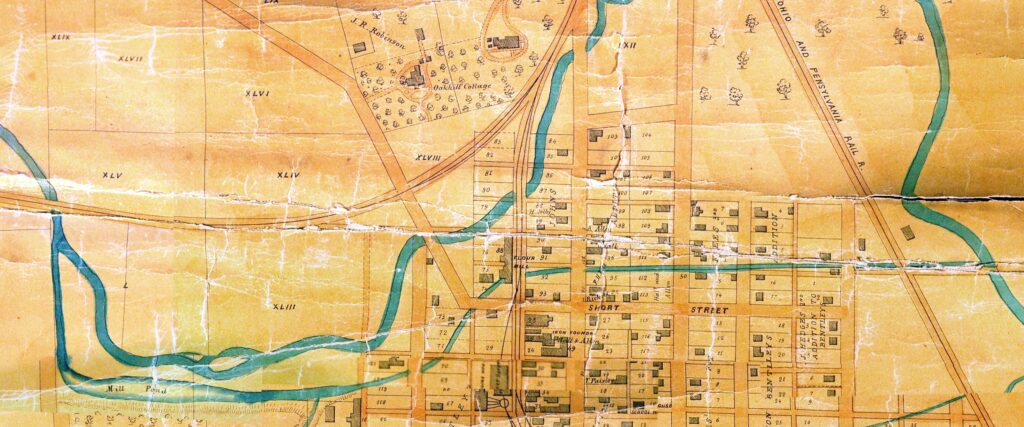

The mill pond began at a dam a half mile west where the railroad crossed Toby’s Run at Bowman Street. The dam diverted Toby’s into a mill pond which hugged the base of the bluff below W. Fifth Street, while the original channel meandered eastward alongside the pond and carried the overflow.

View of the Robinson & Riley Mill from Oak Hill Cottage

Brooker Spring

The mill pond was fed by more than the upstream supply from Toby’s Run. Rising in the middle of the pond was Brooker Spring. Named after the landowner, the spring’s flow was so great that it later became part of Mansfield’s city water supply.

Head and tail races

The pond stretched eastward along the valley. By the time it reached Coul Street, its level was more than 10 feet above the mill at Walnut Street. The channel narrowed at Coul Street, and from there entered a covered culvert as the headrace to the mill. From Coul to the mill, the headrace was 12 feet wide. It was walled up with stone with an arched brick cover according to easements on the land deeds, although the 1853 city map shows it as an open channel. Given the topography, the headrace either went underground or through a deep cut to get through the hill at Coul Street and under Mulberry Street, then emerged and ran on an embankment further on to the mill as the ground sloped away.

The mill sat about where the former Hartman Electric buildings are today, beside a B&O spur that continued across Sixth Street and alongside Walnut Street serving the freight depot, City Mill, and the Sherman & Eminger sash factory.

The tailrace exited the mill and went due east a third of a mile to dump into the Rocky Fork beside Orange Street. This gave the race an extra ten feet of drop as opposed to entering the Toby Run channel. The tailrace was six feet wide, and like the headrace was walled with stone and covered with a brick arch according to the deeds, although not entirely in practice judging by all other evidence of its being a deep open channel along some of its route.

1853 Map of Mansfield, Ohio

Fire

By the 1860s the mill was owned by John Damp who added a steam engine to supplement its waterpower. The entire mill and adjacent warehouse burned down in March of 1869 leaving only an abandoned cellar hole. In 1874 an amusing article in “The Ohio Liberal” (The Government is Best Which Governs Least) decries that a huge unprotected “chasm” remained alongside the B&O tracks, “ready to devour everything that comes within its reach”. The reporter encountered a local who informed him the basement of the old mill had been left “to remind the stranger and passerby of its former usefulness and as an ornament to the locality in which it stood”.

The “mill race

A proposal in City Council in June of 1869 to purchase the rights to the head and tail races of the defunct mill was turned down. Given that the rights had been easements tied strictly to the use of conducting water for running the mill machinery, it would have been a shaky legal proposition to sell the rights for other purposes. So in August of that year, John Damp sent a letter to Council notifying the city that he no longer “uses or occupies the head or tail races” for any purposes and abandoned them. However, the usefulness of the tail race as a storm and sanitary drain crossing the low-lying Flats precluded the abatement of any hazard it presented, so the city continued to deal with the nuisance.

Relative sizes of the head race and tail race. (Miss Mary F. Huber for scale)

Miss Mary F. Huber’s experience falling into its chasm gives us a glimpse into the size and scope of the old mill race long after the mill was gone. Her family’s house stood on solid ground on North Main Street, but the front porch was built over the old race and the distance from the porch down to the race was 18 feet. On the night in question she went out on her porch after a rain storm when a section gave way and precipitated her into the race. She landed at one side of the mill race, barely escaping drowning in the channel that was running eight feet deep at the time.

The same article about Miss Huber states that the race ran under Main Street through a culvert, which was a brick arched tunnel as described in the deed easements. It also says the race had been filled in east of Main Street. The Huber house was at 192 North Main; that was on the east side of Main at the narrow alley that runs along behind the old Cold Storage Building. Sanborn fire insurance maps show nothing of the old race despite the evidence that it was rather conspicuous in some places, enough so to fall into.

A short 1890 news clip reports of a gas line break that caused the occupants of the same house, the Hubers, to evacuate, and it was determined that the gas found its way into the basement through the “old mill race culvert which runs under the house”. Once again, the term “culvert” at that time described a brick arched tunnel such as conducts Ritter Run under the north side of downtown.

Tunnels under the city

City Council throughout this time received and granted requests to tie drains into the old mill race, as well as requests to clean the race for better drainage, and passed resolutions to open the race at its east end into the Rocky Fork when it had become plugged. Therefore the filling in of the race east of Main Street noted in the article about Miss Huber must have referenced filling in over the culvert, given that the race was used as a storm drain at that time, carrying water across the flats to the Rocky Fork.

All that said, how many kids knew about the old mill race culvert, explored it, and passed down their knowledge of mysterious tunnels under the city leading to the Rocky Fork? We know the old race was six feet wide, walled up with stone, and along much of its course was arched over to a height of five feet above the water level. And it ran eighteen feet below street level. A tunnel.

What of the larger, twelve-foot-wide head race? Parts of it may still lurk under the surface from its entrance at Coul Street eastward under Mulberry and north toward the mill.

Previous Post

Previous Post